I would like to begin this week’s Journal with a look at Belkin. Our reading for Belkin this week starts with an excellent look at the theoretical basis behind the cognitive approach to the practices of Information science.

The cognitive approach at its core recognizes that the practice of communication in information science involves cognitive processing on both ends. More specifically Belkin cites De My who holds the view that the cognitive approach involves any kind of information processing (be it perceptual or symbolic) that is mediated by a system of categories or concepts which are a model for the information processor.

The cognitive approach asserts that the states of knowledge, beliefs and so on of people interact with that which they receive, perceive or produce. I think that this is essentially an important idea, especially in the context of the earlier systems based approaches that viewed people basically as passive sponges when it came to interaction with information. What draws me more specifically to the idea is how the concept of states of knowledge, beliefs and so on can be extended further to encompass the concept of a person’s worldview, and the role that the worldview has for people who are interacting with information.

I also visited Brookes this week, who was one of the first to use Cognitivism to develop a strong theoretical framework for information science. Brookes purses an objective (as opposed to subjective) view of Knowledge. However, before we look into his line of thought more closely, it is useful to briefly outline some of the ideas espoused by Popper. Popper refers to the three independent worlds:

1. Physical world

2. The world of subjective mental states or human knowledge

3. World of Objective knowledge – products of the human mind recorded in artifacts

He claims that objective knowledge is the totality of all human thought embodied in human artifacts.

Popper believed that once human knowledge was recorded, it gained a level of permanence, and objectivity (in that aliens may come down and decode our knowledge). Artifacts that record human knowledge become independent of the Author – hence it is no longer subjective and inaccessible but objective and accessible to all who care to study them.

Popper does however maintains that truth is something that we can never knowingly attain and that all our knowledge is always provisional and always open to critique and correction.

I’m not comfortable with some of poppers propositions here. Firstly, While the concept of a ‘third world’ of Objective knowledge sounds appealing to me, I think Poppers attempt to characterize it as a totality of human thought contained in artifacts severely limits the concept. Also, I find his position that truth cannot be attained and that all knowledge is provisional contradictory to the his concept of ‘objective knowledge’. Secondly, the process of recording to and the process of extracting meaning from an artifact entails a subjective process. Going back to Barlow's position, knowledge functions more organically as it is interpreted and reinterpreted, arranged and rearranged given people’s interaction with the artifact, and given their socio-political and historical contexts.

Essentially, I would hold that collective knowledge is not a level closer to objective knowledge due to an attained quality of permanence by recording it into an artifact, it is merely a different form of subjective knowledge that moves around organically.

Brooke regards knowledge as a structure of concepts linked by their relations and information as a small part of that structure – he argues that the knowledge structure can be both objective and subjective.

Brookes developed the following formula -

K[S] + IΔ = K[S + ΔS]

Essentially the formula describes how a knowledge state, when faced with changing information equals new knowledge that is a function of the existing knowledge state and a changing knowledge state.

Brookes suggests that the best way to use this formula is in the interaction between people and objective knowledge – with the purpose of discovering more about subjective knowledge structures. Here, again, we run into the concept of ‘objective knowledge’.

Brookes argues that ‘Potential information’ makes up the world. That there is information out there we cannot detect. Unknown information is objective and as soon as we perceive it, it becomes subjective. Again, when information is contained within a book, it is also deemed as objective as it is 'free' to interpretation.

Again, I find something very appealing about the idea of ‘Unknown Information’ and its relationship to objectivity. I agree with Brookes position here in so far as Unknown (objective information) becomes subjective as soon as we perceive it. However, I find the idea that information can be deemed as objective in an artifact questionable. What is meant by ‘free’ to interpret is problematic here, because the medium in which the information is contained (whether it be the physical medium or the language it is contained in) is subject to an enormous amount of influences that will affect how one will interpret that information – and this is not even to consider the social and historical context of the person who is interpreting the information.

I would like to expand a little on Brookes' statement here: No theory of knowledge is complete without a thorough perspective of consciousness. This statement allows me to entertain the possibility that data is objective and go off on a tangent of abstraction here.

I would like to use the terms Objective Knowledge, Data and potential information interchangeably here to illustrate my understanding.

In my first post I defined data as the the raw input that one receives from outside themselves. I want to now experiment by completely refuting my previous definition to argue that data is precisely that which we cannot receive from outside ourselves. I would like to define data not as segmented packets of potentially informative perceptibility, but rather as a universal indefineability that is excluded from human meaning, understanding and knowledge. That which cannot be known and that which is compromised as soon as it is brought to consciousness.

In this sense, I would argue that the act of Information Processing is in fact the act of destroying data or objective knowledge. The process by which we attribute meaning and rearrange and appropriate data to suit our various sociopolitical and historical contexts is also the process by which that data is divorced from its totality in reality and destroyed - that is, in any attempt to interpret or make conscious data, it no longer exists as data but as information. Thus my point here, is to refute the premise that information is in fact objective, and rather to claim that it is subject to subjectification as soon as one tries to make sense of that which is unknowable (data/objective knowledge).

There are three assumptions that this idea rests on.

1) First, that reality/existence (and non-reality/non-existence) is undefinable. It is a condition beyond duality that encompasses all things (and no things) and all time (and no time).

2) Second, that reality/existence (and non-reality/non-existence) cannot be known through consciousness in it's entirety.

3) Third is the assumption that the essential qualifer for existence is not dependent on ones perception of existence – That is to say, existence and reality (and vice versa) is external to whether we perceive it or not.

Sources

Belkin, N. (1990). The cognitive viewpoint in information science. Journal of Information Science. 16: 11-15.

Brookes, Bertram (1980) The foundations of information science. Part 1: Philosophical aspects. Journal of Information Science 2: 125-133.

Todd, R.J. (2006). "From information to knowledge: charting and measuring changes in students' knowledge of a

curriculum topic" Information Research, 11(4) paper 264. Available at http://InformationR.net/ ir/ 11-4/ paper264.html

Saturday, 25 August 2012

Saturday, 18 August 2012

PIK week 3: Understanding Users - Communities and Contexts

For this week’s post I would like to focus look at two different practical approaches employed by Information Scientists towards information research methodologies and briefly outline the theories underpinning them.

I’ll begin with Louise Limberg’s research paper ‘Experiencing information seeking and learning: a study of the interaction between two phenomena’

Limberg suggests there are three ways of experiencing information seeking and use.

1)

Fact

Finding

2)

Balancing information to make correct choices

3)

Scrutinizing

and analysing

She refers to Phenomenography – which is an approach that explores the different ways that people experience and conceptualize phenomena in the world. She describes Phenomenography as both a set of theoretical assumptions and a methodology – I believe this is an important thing to note, not only to contextualize her research, but for the sake of the research itself. As we discussed in class, all too often do Information scientists take the role of impartial objective observers without being able to make an admission to the fact that they cannot escape their theoretical assumptions underpinning their research.

Limberg cites Marton (1994) when arguing that the Core Concept of ‘conception’ is not a cognitive structure but a way of being aware of something. She highlights Marton’s insistence that Phenomenography is not psychological in character as he claims an experience cannot be placed inside a person – it is a relation between a person and a specific phenomenon – and that the object of a researcher's focus is to account for one as much as the other. I find this approach very interesting, particularly because it ties in well with Barlow’s idea of information as a relationship which I discussed in my previous post.

Limberg also looks into Phenomenography’s assumptions about knowledge as always provisional and essentially qualitative – she states that becoming more knowledgeable about a subject implies a deeper and more complex understanding of a phenomenon on a qualitative level. Further to this, she cites Entwistle’s assertion that learning cannot be separated from learning content. This reinforces the idea of information as primarily a relationship between the person and the thing being interacted with and contrasts heavily with the cognitive approach (which places information outside of the user).

In order to illustrate this contrast, it’s useful to stress the distinction Limberg makes between conceptions that focus on what people experience (a first order perspective) and conceptions that focus on how someone thinks about a specific phenomenon.

The below table illustrates the contrast:

| Cognitive based - User Studies | Phenomenography |

| -a focus on the cognitive processes of the individual | -a focus on how people conceptualize phenomena in the world |

| A first order perspective | -a second order perspective |

Limberg employed a set of interviews and observation sessions of high school seniors for her research. In analyzing her research Limberg takes a hermeneutical approach. She adopts a focus towards analyzing the students’ information seeking and use and a focus towards their understanding of the subject matter.

Through a process of several cases of reading and reflexion, possible patterns and categories of conceptions to describe phenomena are discerned. The students’ conceptions of information seeking and use and their conceptions of subject matter where then compared.

Her research makes the following conclusions:

a)

Students’

conceptions of how to use and seek information is not independent of content.

b)

Interaction

between information seeking/use and learning primarily concerns the use of information

c)

Group

Patterns strongly influence both info seeking, information use and the learning

process.

The

fist conclusion contradicts the established view in the Information Sciences of

information seeking as a general process divorced from content.

The

second conclusion could also be interesting given that traditional forms of

user studies focus heavily on information seeking as opposed to information

use. Given that Limberg’s study looked into both information seeking and use to

arrive at this conclusion, it may have implications on the field of information

science to have a stronger focus on information use and bring a balanced

perspective to Information science research.

Finally,

it seems that a phenomenographical approach is well suited to researching the

influence of groups on information seeking and use – it would be interesting to

look into cognitive based user studies as a point of contrast to see how

effective a cognitive approach would be in researching the effects of groups on

information seeking, use and the learning process.

Interestingly, its focus is on the question of how theater professionals make sense of Shakespeare and it reveals some interesting facts about the information behavior of these professionals that I hardly think an individual focused research approach would be able to come to.

Dr Olsson’s findings revealed that participants attached a lack of importance to active information seeking with only a few who reported it as an important part of their sense-making. The few who did actively seek out academic literature relating to Shakespeare overwhelmingly described it as an activity they undertook in the background or between productions. Furthermore texts were far more likely to be chosen as the result of a personal recommendation from a colleague than active information seeking. Respondents describe that their colleagues or mentors and interactions during rehearsals were the greatest source of influence over their understanding of Shakespeare.

Such findings have serious implications for a field that seems to have put such a heavy emphasis on individual information behavior and active information seeking in the past.

What is of particular interest to me here however, is the methodology used to arrive at these findings. As with the theoretical underpinnings to the study, the methodology also drew from a variety of fields. It begun with Dervin’s life-line technique (admittedly a technique I’m not too familiar with) but became increasingly influenced by the less structured and conversational approach by Seidman. Dr Olsson mentioned during the lecture that initially respondents were reluctant to be interviewed by an academic, and this illustrated the kind of relationship that theater professionals had with literary academics. The interviewing technique allowed some respondents to feel like they hadn't even been in an interview, and such a framework allowed respondents to be more open and create less barriers during the interviewing process.

I believe there was more to it than this however, as something occurred to me when Dr Olsson, during the lecture, reported that some respondents even found it a very insightful interview which revealed a lot about themselves. To illustrate the point however, I'd like to refer to a philosopher I hold in very high regard: Donald Rumsfield.

Mr Rumsfield, despite his supreme understanding of how knowledge and information functions, does leave one component out in his classification of knowledge - That is, among the known knowns, the known unknowns and the unknown unknowns, there is also the unknown knowns. That is, the ethical and sociopolitical prejudices that influence our actions without our even being conscious of them. Zizek illustrates this point in a talk at the 3:37 mark where he talks about ideology:

What particularly interests me here about Dr Olsson's methodology is its ability to reveal the ‘unknown knowns’ within its respondents. For the ability to reveal the underpinning assumptions and ideology behind an information behaviour is fundamental, I would argue, to understanding their relationship to information.

Sources

Buckland, M. (1991) Information as Thing. Journal of the American Society for Information Science. 42 (5), 351-360.

Olsson, M. (2009) Re-Thinking our Concept of Users. Australian Academic & Research Libraries 40 (1): 22-35.

Wilson, T. (2000). Human Information Behaviour. Informing Science 3 (1), 49-55.

Sunday, 12 August 2012

John Perry Barlow - The Economy of Ideas

When Professor Olsson mentioned John Perry Barlow and some of ideas he talks about in class, it immediately perked my interest. So much so that I've decided to dedicate a post specifically about him. I should stress here that I probably do hold some favorable bias towards him given his position as a digital rights activist and given the fact that he was one of the co-founders of the Electronic Frontier Foundation.

Although I won't be focusing too much on his position on intellectual property rights, patents and copyright laws I would like to shed light on how he views information should be understood. Let me, however, begin with a breif outline on his thoughts about the history of intellectual property.

Barlow argues that traditionally property law of all sorts has found its definition in the realm of the physical world. However, with digital

technology, information is now becoming detached from the physical plane and the laws of the past are struggling to cope with this phenomenon.

He asserts that when we look at the history of intellectual property law, the thoughts of thinkers that could be capitalized have been focused on the expression of ideas. The ideas themselves, as well as facts about the phenomena of the world, were considered to be the collective property of humanity. For all practical purposes, the value was in the conveyance and not in the thought conveyed.

He asserts that when we look at the history of intellectual property law, the thoughts of thinkers that could be capitalized have been focused on the expression of ideas. The ideas themselves, as well as facts about the phenomena of the world, were considered to be the collective property of humanity. For all practical purposes, the value was in the conveyance and not in the thought conveyed.

I find this very interesting as it allows me to think of our primary relationship with information as not our ability to own it (in our minds), but rather our ability to rearrange it into different forms. Information is not to be seen as compartmentalized packets that can be stored by the mind, but as an constantly changing entity of connections that is transformed and rearranged through the vessels of our minds. I think there is a connection here with this way of thinking about information and the question about the relationship between knowledge and meaning. As we process and rearrange information to suit our specific situation and broader context, meaning is assigned to information and is then negotiated in the public sphere (arguably, the whole purpose of this reflective journal is to take information from various sources, re-arrange it in a way that makes meaning to me personally, and then negotiate its meaning publicly).

For now, I would like to focus on Barlow's Perspective when it comes to making sense of what information is. He ascribes three separate properties to Information:

1) Information is an activity

2) Information is a life form

3) Information is a relationship

Information is an Activity

Information is an Activity

Expanding on the first property, he describes information as something that happens in the field of interaction between minds or objects or

other pieces of information. He describes it as an action which occupies time rather than a

state of being which occupies physical space (in contrast to Buckland's view of information as an object). In Barlow's words; "it is the dance, not the dancer". In addition to this, he regards information as an experience as opposed to a possession, that regardless of whether information is stored in a virtual abstract medium like the internet or in a physical product like a book, a person must decode and process this information as an experience - it is not enough to merely own the object. Barlow also maintains that information that isn't moving or interacted with (information that is hoarded) ceases to exist.

Information is a Life form

For the second property, Barlow makes the uncanny claim that information literally is a life form in almost all respects except for the fact that it doesn't rely on carbon in its make up. Barlow cites Richard Dawkins' (an evolutionary biologist) proposal of "memes" - which are self replicating patterns of information that replicate and spread themselves across the minds of individuals and society. Dawkins described in his book The Selfish Gene the concept that the phenotypic effects of a gene are not necessarily restricted to an organism's itself, but can spread far into the environment, including the bodies of other organisms or in our case, into society and culture.

In the communicative medium of the internet, where the barriers to information transference between people are broken down, there is clear evidence of the 'meme' phenomenon. There are even dedicated databases that track the origins and propagation of memes throughout the internet:

http://knowyourmeme.com/memes

However The idea that an 'idea' can have a desire, is a difficult one to grasp for me - despite the fact I find that this idea itself seems to be making it's own way into my mind of its own accord. Yet maybe my attempt to grasp the idea is the problem in the first place. If I am to understand ideas as a self-contained entity then maybe the most efficient way to make sense of it is to establish discourse with others in an attempt to propagate the idea and negotiate its meaning.

Another interesting perspective that Barlow brings to the table is his assertion that Information, just like life, is perishable. Information quality degrades rapidly both over time and in distance (or separation) from the source of production. This again contrasts sharply with Wilson who thought of Information as objective and what not

Information is a Relationship

Finally, Barlow addresses the importance of meaning when talking about Information as a relationship.

Barlow argues that the way information is transmitted to reception is strongly dependent on the relationship between the sender and the receiver. He argues that each communicative relationship is unique, and that receiving information can be as creative as transmitting it. He also refers to 'receptors' in the receiver as important to render a transmission of information meaningful - that is things like shared terminology, language, paradigm, interest and the attention that the receiver must have in order render more meaning to a transmission.

Admittedly, there has been a woefully small amount of critiquing Barlow's positions here, undoubtedly due to the fact that I find myself agreeing with most of his ideas - however it will be interesting to see how Barlows Ideas will contrast with course content that I will come across later down the track.

Sources

Barlow, John Perry (1994) A Taxonomy of Information. Bulletin of the American Society for Information Science.

Friday, 10 August 2012

PIK Week 2 - Key Concepts: What is Information? Knowledge?

I would like to begin today's journal by looking into

T.D, Wilson's work: Human Information Behavior.

Without beginning my analysis with too much of a critique, I would like to note that Wilson has made a very important contribution to Information science. Wilson drew attention to the fact that information science was only one of the disciplines that dealt with the subject and he gave examples of a number of fields that contained relevant work. He drew attention to useful models, theoretical concepts and research instruments that might be employed in future work from an Information Science perspective and consequently had a significant impact on the field of Information Science as we know it today.

His article; Human Information Behavior is a good one to begin with as it goes over baseline definitions and visits various theories that are prominent in Information Science today.

Without beginning my analysis with too much of a critique, I would like to note that Wilson has made a very important contribution to Information science. Wilson drew attention to the fact that information science was only one of the disciplines that dealt with the subject and he gave examples of a number of fields that contained relevant work. He drew attention to useful models, theoretical concepts and research instruments that might be employed in future work from an Information Science perspective and consequently had a significant impact on the field of Information Science as we know it today.

His article; Human Information Behavior is a good one to begin with as it goes over baseline definitions and visits various theories that are prominent in Information Science today.

Wilson defines information as a piece of datum that is capable of informing a user. He goes into further detail by identifying four definitions of behavior that users utilize to subsume data into information:

He defines Information Behavior as a general term that defines the totality of human behavior as it relates to all sources and channels of information.

He defines Information Seeking Behavior as the intention of a user to seek out information due to a need to satisfy a goal or objective.

He defines Information Seeking Behavior as the intention of a user to seek out information due to a need to satisfy a goal or objective.

He defines Information Searching Behavior as the ‘micro-level’ techniques

that users employ in their search for information from information systems of all kinds.

that users employ in their search for information from information systems of all kinds.

And he defines Information Use Behavior as the physical and mental acts involved in bringing together the information found into the person's existing knowledge base.

He also maintains that Knowledge can only be known by the knower, and that only information can be transmitted.

Although these definitions seem useful as the building blocks for the field of information science I can't help but feel they are limited on several levels. It sounds as though the term 'Information Behavior' is used by Wilson in a context limited strictly to the field of information and library science. However, the 'totality' of information behaviour as it relates to all sources of information could potentially be anything - and I don't get the sense that Wilson is encompassing the full scope of the word (would Wilson, say, be inclined to define someone's interaction with smell of milk as information behaviour?). Furthermore, in contrast to his rather broad definition of Information use, his definitions regarding information seeking/searching seem very specific and precise (revealing Wilson's strong focus towards a more active form of information interaction). Finally, I'm not sure I completely agree with his position that Knowledge can only be known by the 'knower'. To me, this position indicates that Knowledge is an objective entity divorced from meaning that can be held only within an individual. I would much prefer to visit and the wider social influences on knowledge and our relation to it before I accept Wilson's position. It also raises the question of how meaning is created in relation to knowledge which came up in my previous post.

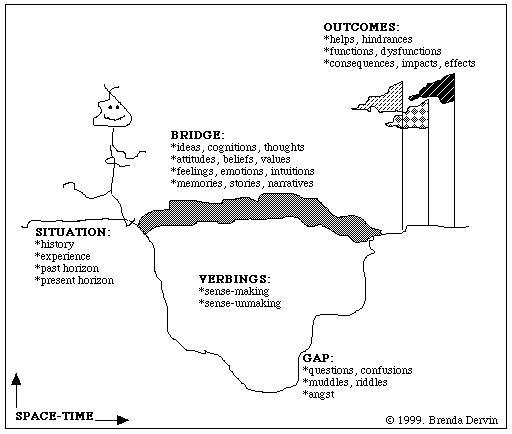

Wilson visits Dervin's sense-making approach in the article. The fact that Dervin's work has been so influential in the Information Science field and given that it is first time I've been exposed to it, I thought it apt to bring up the theory here. I found an excellent illustration by Dervin herself which illustrates the ideas of sense-making:

For someone who has changed the face of discipline towards a more user centered approach, Dervin has certainly put a lot of effort into illustrating the user in the above model. But more to the point, what is particularly interesting about this model is its much more holistic approach to information. A model which I'd argue would be much more capable of predicting 'information behaviour' as defined above by Wilson.

Wilson also briefly touches on multidisciplinary approaches to information science, by visiting research on cognitive, marketing and healthcare oriented approaches to information science (Cacioppo, Petty & Kao (1984), Timko and Loyns (1989) and Krohne (1993) respectively). He concludes that the study of human information behavior has become well-placed within information science. I feel that this focus on people as opposed to a systems oriented approach (as was the focus in the discipline earlier) opens up the field to a broad collection of theories and approaches that will ultimately help move the field forward.

It is worth analyzing why I feel this way. I believe that the more diversity of approaches and theories a field contains, the more likely it will be to yield a resilience to the knowledge that characterises it. A field with diverse theories and approaches will be more likely to contain contradictions and oppositions and I argue that these qualities are an important factor in developing progressive knowledge. My perspective here is strongly influenced by Hegel, and more over a Zizekian interpretation of Hegel's concept of Aufhebung (or sublation). Zizek claims that it is not a matter of having one pole, then the other pole, and through the meeting of these poles we arrive at a broader perspective and bring them together through synthesis. He claims that for Hegel it is not about re-establishing the symmetry and balance of the two opposing principles, but to recognize in one pole, the symptom or the failure of the other.

Where Wilson is trying to synthesize all the different approaches and theories under a balanced framework, I would argue that it is more important to in fact draw an opposite conclusion. Wilson argues that there is evidence that shows "some degree of integration of different models is now taking place." (he even goes on to cite his global model as a way of integrating the field). I would argue that precisely his ability to develop such a 'global' model of the field is evidence that these 'integrated' approaches and theories can now start to be described as hegemonic and that it is important that the field should focus towards opening up more opportunities to accommodate different and opposing theories and approaches.

In an earlier publication, Wilson (1994) identifies that " a great deal of user behavior is dependent upon the nature of the system being used." He goes on to say that "Any integrated, theoretical model must also find a place for the changing character of information systems." What is interesting to me here is the relationship between integrated models and the information systems it creates. Furthermore, I would argue the 'integrative' model ought not to be about accommodating for the changing character of information systems, but rather the field should accommodate for opposing models that challenge this 'integrative' model that is gaining so much acceptance across the field.

Moving on from Wilson, I wouldn't be able to complete this week's journal without a critical look at Buckland's article as well - especially after the active discussion in class about the idea of information as a 'thing'.

Buckland makes interesting distinctions when referring to information:

Information as a Process (the act of informing - becoming informed),

Information as Knowledge (information that serves to reduce ignorance and uncertainty) Information as a Thing (an object through with Information as knowledge can be accessed)

Information as Data Processing (When data is processed in an information system)

Buckland makes interesting distinctions when referring to information:

Information as a Process (the act of informing - becoming informed),

Information as Knowledge (information that serves to reduce ignorance and uncertainty) Information as a Thing (an object through with Information as knowledge can be accessed)

Information as Data Processing (When data is processed in an information system)

I find the first three of these distinctions problematic. First of all, thinking of information as a process is a difficult one to get my head around - I want to be careful here and not simply limit my understanding of 'information as a process' to 'learning'. I'd like to think of it as a much broader and all encompassing process that involves a person's interaction with the world around them.

Secondly, I find the idea that knowledge is simply that which reduces ignorance or uncertainty rather limited. Again the assumption here seems to be that knowledge is a objective abstraction that is devoid of meaning - an assumption that I'm not readily willing to accept. Furthermore, where does 'misinformation' fit in Buckland's idea of information? or does he not regard misinformation to influence knowledge at all?

Finally, I find the idea of information as a physical thing problematic. Fundamentally, information objects (as Buckland describes them) are MEDIUMS through which information is accessed, they are not information themselves. Though the medium has a lot of influence in the way information is understood by people, I would be reluctant to say that the Medium itself is information.

Buckland does raise an interesting point about original artifacts and I would hold these as separate from 'information objects'. Clearly, when one interacts with, say a dinosaur bone, this is a more direct relationship with information then a representation of a dinosaur bone in a book. Of course the situation and context in which a person interacts with such a piece of information must be taken into account but I'm inclined to believe that there is a clear distinction between this direct relationship with information and information that has been re-interpreted, reproduced and appropriated by someone else through a text. I argue that the original relationship between the subject and the object is compromised through the act of communication.

Professor Olsson also introduced John Perry Barlow in class and I am finding his ideas extremely appealing. So much so that I think the ideas he talks about deserve a separate post. I'll finish up this post with a lecture by Barlow introducing some of the ideas he talks about:

Sources:

Buckland, J. P. (1991) Information as a Thing. Journal of the American Society for information Science, 42 (5), 351-360.

Cacioppo, J. T., R. E. Petty, et al. (1984). The efficient assessment of

need for cognition. Journal of Personality Assessment, 42, 306-

307.

need for cognition. Journal of Personality Assessment, 42, 306-

307.

coping research. Attention and Avoidance: Strategies in Coping

with Aversiveness. H. W. Krohne. Seattle, Hogrefe and Huber:

Chapter 2.

Timko, M. & R. M. A. Loynes (1989). Market information needs for

prairie farmers. Canadian Journal of Agricultural Economics, 37,

609-627.

Wilson, T. (2000). Human Information Behaviour. Informing Science 3 (1), 49-55.

Wilson, T.D. (1994). Information needs and uses: 50 years of progress?

In: Vickery, B.C. (ed.), Fifty years of information progress: a Journal of Documentation Review, 15- 51 London: ASLI

Friday, 3 August 2012

People, Information and Knowledge: An Introduction

Welcome to People, Information and Knowledge: A Reflective Journal.

This online journal aims to develop an understanding of Information and Knowledge in a very broad context (economic, psychological, political, metaphysical, social, etc).

The Journal will frequently refer to readings and tutorials I'll be attending for my Information and Knowledge Management course that I'm currently studying and will be an assessable component of one of my subjects; People, Information and Knowledge.

The Journal will have a general focus around the field of information science: an interdisciplinary field primarily concerned with the analysis, collection, classification, manipulation, storage, retrieval and dissemination of information.

The first session of my People, Information and knowledge subject, Professor Michael Olsson challenged some of the more traditional and mainstream conceptions of what constitutes information and knowledge.

Some initial ideas were presented in the lecture that caught my interest.

Firstly, the idea that knowledge is not solely a cognitive process that

resides within our brains. As far as I can understand, because thought is ingrained in language, and the development of language as a system is dependent on wider socioeconomic and political factors, it cannot be said that knowledge is solely contained in the realm of thought or at least that it cannot be separated from knowledge and information. This is an idea I find very attractive, however it is also a controvertial one as it flies in the face of this man:

Rene Decartes' "Cogito ergo sum" is a phrase that characterises Rationalism over Aristotelian notions of empiricism. That is, the idea that the world can only be known through reasoning and not through sensory experience. Rene Descartes and the consequent rise of Rationalism is responsible for much of the scientific revolution and Western Thought that followed in the past few centuries. To challenge this basic idea is to challenge the pillars upon which much of Western Civilization rests on today.

This challenging idea - as I understand it - is that context plays a large part in determining meaning and hence shaping knowledge. This raises a further question which is probably worth revisiting when I'm better equipped to deal with it: What exactly is the relationship between meaning and knowledge?

We also covered the way that a person’s multiple social roles and

identities influences the way they engage with information. This raises

important questions about ethnocentrism in our educational institutions – we

discussed IQ tests for example, and how socio-political factors had a role in

influencing the outcome of what individuals scored.

Professor Olsson also raised the very important point that it is always important to question the assumptions behind which a given context (or system) is based on. In the formation of a social system (whether it be a whole language or a simple IQ test), the creators operate on a set of assumptions that their pre-existing perspectives are correct - these assumptions serve to treat people within the system in a patronising way. This raises a whole lot of questions about power relations and hegemony when considering the way information and knowledge functions, which will hopefully be addressed in later lessons. It would be particularly interesting to explore the role that ideology has, and the way it relates to those who

create systems within their respective socioeconomic contexts.

The more difficult concept to grasp for me at the moment is

the idea that information is about the relationship between a person

and an object and is to be seen as a process as opposed to a thing. Given a certain context, the relationship between a person and a subject forms meaning - I am assuming that it is essentially about the negotiation that occurs to formulate meaning between:

a) The Person

b) the Subject

c) the overarching system in which this process is occuring

a) The Person

b) the Subject

c) the overarching system in which this process is occuring

We

were given some words to define as a task in the last class. What I’d like to

do is define these terms in a very simplistic and traditional way

with the conscious intention to have my ignorant conceptions of these terms now contrast sharply with my conceptions of them after I've been exposed to the entirety of Professor Olsson's subject. Also, there are things we say we believe, and the things we practice, and I'm hoping that a quick and uninhibited definition of these terms may help reveal any assumptions I might have about what these terms mean.

Data: The Raw input that one receives from outside themselves.

Information: A classified and formalised form of data

Knowledge: A designated meaning assigned to information that has become accepted.

Power: the capability to realise a desire or purpose

Information

Need: A person's purpose to attain a specific component of information.

Information

Use: A person who interacts with a given component of information.

Information

Poverty: A person who is unable to attain a specific component of information based on their information need.

Information

Professional: A person who deals in the business of satisfying the information needs of a client or user.

What

is

particularly exciting about this subject is that I see an excellent

opportunity to integrate

themes which I have been very interested about before beginning this

course. I have an

interest to develop a strong connection between the themes of Ideology,

Systems/Networks and Information Security/Privacy and my initial

impression is that this course and reflective journal will be an

excellent opportunity to achieve such an aim.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)